- 1:34 PM (IST) 20 Jan 2026Latest

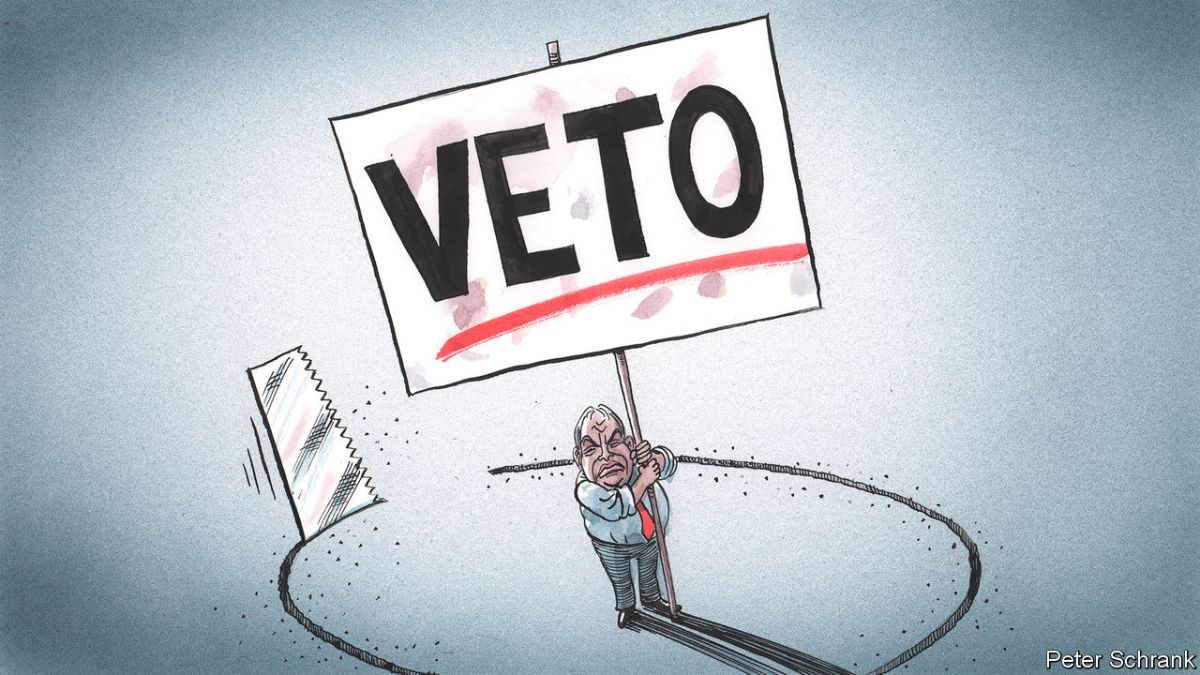

Europe live legal updates: Claims of a United States veto expose a profound legal fiction

The claim by Nigel Farage that Donald Trump has “vetoed the surrender of the Chagos Islands” is not merely politically charged rhetoric. It is legally incoherent, constitutionally impossible, and geopolitically destabilising. Yet its emergence at this precise moment, amid a wider confrontation over Greenland, tariffs, and the future of the rules based international order, reveals something more troubling than domestic posturing. It illustrates how international law, decolonisation obligations, treaty making powers, and the rights of displaced peoples are being deliberately misrepresented to legitimise a return to power politics.

The claim by Nigel Farage that Donald Trump has “vetoed the surrender of the Chagos Islands” is not merely politically charged rhetoric. It is legally incoherent, constitutionally impossible, and geopolitically destabilising. Yet its emergence at this precise moment, amid a wider confrontation over Greenland, tariffs, and the future of the rules based international order, reveals something more troubling than domestic posturing. It illustrates how international law, decolonisation obligations, treaty making powers, and the rights of displaced peoples are being deliberately misrepresented to legitimise a return to power politics.

Farage, leader of Reform UK and a close political ally of Trump, announced on social media that he was grateful the United States president had blocked the United Kingdom’s agreement to cede sovereignty over the Chagos Islands to Mauritius. His party has vowed to overturn the agreement, denouncing it as a costly act driven by what it calls postcolonial guilt and by a government allegedly “run by human rights lawyers”.

Every element of this narrative collapses under legal scrutiny.

To begin with the most basic point, the President of the United States has no constitutional, statutory, or international authority to veto an agreement concluded between the United Kingdom and Mauritius. Treaty making and territorial sovereignty fall squarely within the domestic constitutional competence of the United Kingdom and the sovereign equality of states under international law. Article 2 of the United Nations Charter enshrines the principle that all states are legally equal and that none may intervene in the internal or external affairs of another.

There exists no mechanism in international law by which a third state, even a superpower, can nullify or veto a bilateral treaty concerning territorial sovereignty between two other states.

If Trump has expressed political opposition, diplomatic displeasure, or strategic concern regarding the Chagos agreement, that is a matter of foreign policy advocacy. It is not, and cannot be, a veto in any legal sense.

The distinction is not technical pedantry. It is foundational. To describe such opposition as a veto is to imply a hierarchical international system in which certain states possess supervisory authority over the sovereignty decisions of others. That concept was rejected in 1945 and is incompatible with the modern law of nations.

The Chagos agreement itself is the product of binding legal pressure, not ideological sentiment.

In 2019, the International Court of Justice issued an advisory opinion concluding that the United Kingdom’s continued administration of the Chagos Islands constituted a wrongful act because the territory had been unlawfully detached from Mauritius during decolonisation. The Court held that the United Kingdom was under an obligation to bring its administration to an end “as rapidly as possible”. The United Nations General Assembly subsequently endorsed this position by an overwhelming majority.

While advisory opinions are formally non binding, their legal authority is immense. They represent the most authoritative statement of international law available short of a contentious judgment. No responsible government could ignore such a finding without accepting that it was acting in continuing breach of international law.

Against this background, the 2025 agreement to transfer sovereignty to Mauritius while leasing Diego Garcia for 99 years to maintain the United States United Kingdom military base was not an act of charity or guilt. It was an act of belated legal compliance.

Farage’s assertion that the agreement is fuelled by postcolonial guilt mischaracterises a binding legal obligation as an emotional indulgence. This is not merely inaccurate. It is strategically dangerous, because it reframes compliance with international law as weakness, and illegality as strength.

The invocation of “human rights lawyers” as a term of derision is equally revealing. The displacement of up to 2,000 Chagossians in the late 1960s and early 1970s to facilitate the construction of the Diego Garcia base is widely recognised by scholars, United Nations bodies, and courts as a grave violation of fundamental human rights. It involved forced removal, denial of the right to return, and decades of legal obstruction. Describing efforts to remedy these wrongs as ideological activism is to deny the existence of legally enforceable rights.

The financial elements of the agreement further demonstrate its juridical, not sentimental, character. The United Kingdom committed to a fund of £40 million for displaced Chagossians and to annual payments of at least £120 million to Mauritius over 99 years, amounting to at least £13 billion in cash terms. These sums are not acts of contrition alone. They are part of a negotiated settlement designed to extinguish international legal liability, stabilise long term military access, and close a chapter of unlawful colonial administration.

It is here that the intersection with Trump’s wider strategy becomes impossible to ignore.

Trump has already characterised the United Kingdom’s decision to cede the Chagos Islands as an act of “great stupidity” and as proof of European weakness, citing it as justification for his insistence that Greenland must be acquired by the United States. He has explicitly argued that territory should be retained or seized for strategic reasons regardless of international legal process.

This worldview is coherent in only one sense: it rejects the post war legal order entirely.

If the Chagos agreement were to be overturned on the basis that decolonisation is optional, that advisory opinions of the International Court of Justice are disposable, and that sovereignty may be maintained by power alone, then the same logic would legitimise the forced acquisition of Greenland, the coercion of Denmark, and the use of tariffs as instruments of territorial extortion.

Farage’s statement therefore functions as more than domestic opposition to a controversial agreement. It aligns British political discourse with an emerging doctrine that sovereignty is conditional, human rights are negotiable, and international adjudication is irrelevant.

From a strictly legal perspective, any attempt by a future United Kingdom government to unilaterally reverse the Chagos agreement would trigger severe consequences.

It would constitute a breach of treaty obligations to Mauritius under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. It would revive the state of illegality identified by the International Court of Justice. It would expose the United Kingdom to renewed proceedings before international tribunals. It would undermine the legal security of the Diego Garcia base itself, because its operation would once again rest on disputed sovereignty rather than lawful lease.

It would also place the United Kingdom in open defiance of the United Nations General Assembly and the near unanimous position of the international community.

As for any alleged United States veto, such a concept belongs not to law but to imperial nostalgia.

Even the United States Security Council veto, often misunderstood, applies only to resolutions of that body and cannot authorise the alteration of territorial sovereignty by force or coercion. The idea that a United States president can block decolonisation agreements between third states is an invention with no legal foundation.

The danger lies not in the statement itself, but in its normalisation.

When senior political figures describe unlawful occupation as pragmatism, and compliance with international law as weakness, they train the public to view legality as a matter of preference rather than obligation. In doing so, they erode the very structures that protect medium sized states such as the United Kingdom from the predations of greater powers.

There is a deep irony here.

The same political movement that claims to defend British sovereignty is endorsing a worldview in which sovereignty is contingent on the approval of Washington. To celebrate an imagined American veto over British treaty making is to concede, rhetorically and conceptually, that the United Kingdom is not fully sovereign.

In legal reality, the Chagos agreement remains binding unless lawfully terminated in accordance with its own provisions and international law. Trump cannot veto it. Farage cannot repeal it by declaration. And no amount of rhetorical disdain for human rights lawyers can alter the binding force of international obligations.

What is unfolding is not merely a dispute over islands in the Indian Ocean. It is a contest between two incompatible visions of world order.

One holds that territory, trade, and human beings are subject to law.

The other holds that they are subject to power.

Markets have already reacted to this second vision in the context of Greenland and tariffs. Courts and diplomats will soon be forced to confront it in the context of Chagos.

The outcome will determine whether sovereignty remains a legal status protected by rules, or a bargaining chip to be traded, vetoed, or seized at will.

In that sense, the most dangerous element of Farage’s claim is not that it is wrong, but that it seeks to make the wrong seem normal.