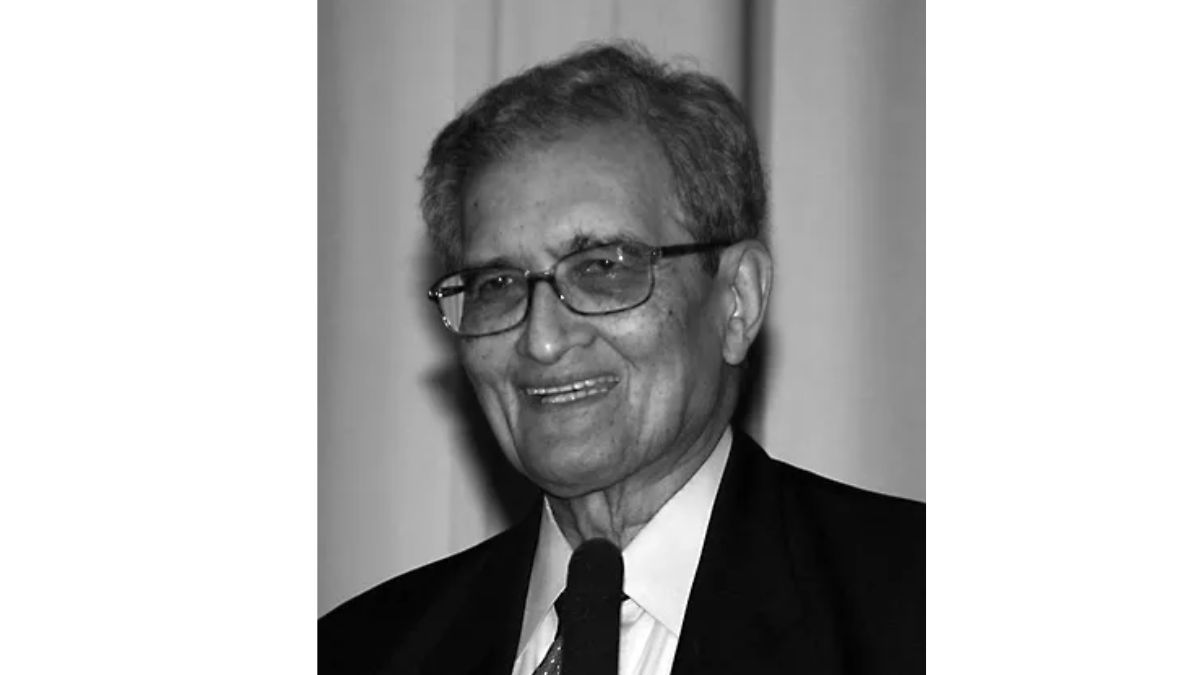

Nobel laureate Amartya Sen has delivered a withering legal and democratic critique of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls in West Bengal, calling the exercise “unjust to voters” and “unfair to democracy” because it is being conducted in undue haste mere months before critical assembly elections. His intervention raises profound questions about constitutional rights, due process, and the rule of law in India’s electoral democracy.

At its core, Sen’s argument is not merely academic. It strikes at the legal foundations of universal adult franchise a right guaranteed by the Constitution and the obligations of the Election Commission of India (ECI) to uphold democratic participation without erecting undue barriers.

Electoral rolls and the rule of law: legal cornerstones at stake

Under Article 326 of the Indian Constitution, every adult citizen has the right to vote in elections based on universal adult suffrage, subject only to reasonable restrictions laid down by law. Reasonableness is not a mere cliché in constitutional jurisprudence: it demands procedural fairness, transparency, and adequate opportunity for citizens to assert their electoral rights. Sen’s contention is that the SIR, as conducted, sharply deviates from these legal imperatives.

The Supreme Court of India has consistently held that electoral roll revisions are a legitimate administrative function when executed with fairness. But “administrative function” cannot become an excuse for abridging participation rights. The legal benchmark is clear: procedures must not impose unjustifiable burdens on voters, especially vulnerable populations who may lack documentation.

Time pressure and due process: A constitutional litmus test

Sen’s personal experience during the SIR being asked to justify his voting entitlement due to an alleged “logical discrepancy” in his and his deceased mother’s entries is telling. Even seasoned observers and officials were reportedly overwhelmed by time constraints. Yet a rushed exercise with compressed timelines raises the spectre of procedural unfairness.

In legal terms, due process demands that eligible voters are given sufficient time and clear procedural avenues to establish their right to be on the electoral roll. A hurried roll revision that leaves little room for corrective action arguably fails this test, potentially violating key constitutional guarantees of equality before the law under Article 14 and the right to participate in public affairs under Article 326.

Disenfranchisement and structural inequality: Who bears the burden?

Sen’s concerns extend beyond mere administrative glitch to systemic exclusion. Many Indian citizens born in rural areas like Sen himself lack official birth certificates or other documentary proof of eligibility. Legal systems worldwide treat lack of documentation as a formal barrier to rights, not a determinant of qualification. A process that inadvertently penalises the underprivileged or those without easy access to documentation risks embedding class bias into the democratic process.

This is not a theoretical abstraction. If voters are excluded because they cannot swiftly produce documents or navigate bureaucratic hurdles, the State risks creating a democracy with qualifications, not rights a notion antithetical to constitutional promise.

The election commission’s obligations and judicial review

The ECI, as a constitutional body entrusted with conducting free and fair elections, has the legal duty to ensure that procedures do not disadvantage any group of voters. As Sen emphasises, even officials appeared to struggle with the compressed timeline, signalling institutional strain rather than administrative precision.

In such contexts, judicial review becomes a critical safeguard. The Supreme Court has often intervened when electoral procedures have the potential to disenfranchise voters, holding that electoral fairness is integral to the democratic fabric. If the SIR’s timeline indeed constitutes a barrier to voter participation, affected individuals or civil society actors could seek judicial redress on grounds of violation of fundamental rights.

Political implications and the risk of partisan advantage

While Sen refrains from offering definitive claims about which political party might benefit from the SIR process, he does suggest that procedural flaws should not be allowed to persist simply because one side might gain. This reflects a core legal and democratic principle: electoral procedures must be neutral and non-partisan.

Any perception that administrative actions are skewed even unintentionally undermines public confidence in electoral integrity, which is itself a constitutional value. In a democracy, legitimacy flows not just from outcomes but from transparent, fair processes.

Minority rights and the question of equal protection

Sen’s remarks also touch on how structural inequalities can disproportionately affect vulnerable groups, including minorities. While the Constitution guarantees equality of status and opportunity (Article 15), administrative processes that demand documentation disproportionately burden those traditionally marginalised, such as economically weaker sections and minority communities.

This raises a compelling legal question: can a well-meaning administrative revision process inadvertently trigger exclusion that conflicts with constitutional guarantees of equality and nondiscrimination?

A democratic alarm bell that cannot be ignored

Amartya Sen’s critique of the West Bengal SIR process is a legal clarion call. It reminds us that the essence of democracy is not elections on a calendar but elections with fairness, inclusion, and dignity for every voter.

When electoral administration imposes undue time pressure and documentation hurdles, it moves perilously close to unconstitutional disenfranchisement. At that point, legal scrutiny is not merely appropriate it is indispensable.

In a country where democracy is enshrined as a living, breathing ideal, procedural haste cannot become a substitute for procedural justice. The SIR debate is not simply about rolls and deadlines; it is about the very legitimacy of the democratic state and its fidelity to the rule of law.