The United States Justice Department’s request that a federal judge deny the appointment of a special master to oversee the release of Jeffrey Epstein related records has reopened one of the most legally and institutionally sensitive debates in modern American justice. At stake is not merely the pace of disclosure, but the boundaries of judicial authority, legislative intervention and executive control over criminal records tied to one of the most notorious abuse cases in recent history.

While the department frames its position as a straightforward question of law and procedure, critics argue that the resistance reflects a deeper discomfort with independent oversight in a matter where public trust has long been eroded.

The core dispute: Who has the right to intervene

At the centre of the controversy is a request by US Representatives Ro Khanna and Thomas Massie for the appointment of a special master to independently supervise the public release of Epstein related documents. Their argument rests on a statutory requirement obliging the Justice Department to release all Epstein records by December 19, a deadline the department has acknowledged it cannot meet in full.

The Justice Department’s response is legally orthodox but politically charged. In a letter to US District Judge Paul Engelmayer, Attorney General Pam Bondi and Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche argue that the lawmakers lack standing, are not parties to the criminal proceedings in United States v Ghislaine Maxwell and therefore have no right to seek relief from the court.

From a strict doctrinal perspective, the department’s argument is difficult to dismiss. Federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction. Standing requires a concrete and particularised injury, not generalised dissatisfaction with executive action. Members of Congress, acting in their legislative capacity, rarely satisfy this threshold.

Yet this formalism does little to quiet broader concerns about accountability.

The role and limits of a special master

A special master is not a routine appointment. Courts typically deploy them in complex or sensitive cases where independent review is necessary to protect privilege, privacy or procedural fairness. The Trump era Mar a Lago documents litigation demonstrated how controversial such appointments can be, particularly when they appear to encroach on executive prerogatives.

The Justice Department insists that there is no legal authority for the court to impose a special master in this context, especially at the request of non parties. It also contends that the role sought by the lawmakers is inconsistent with the traditional function of an amicus curiae, whose purpose is to assist the court, not direct executive compliance.

Legally, this position is sound. Institutionally, however, it raises uncomfortable questions about whether existing mechanisms are adequate when disclosure obligations collide with bureaucratic inertia.

Five point two million pages and the politics of delay

The department’s own disclosures have fuelled scepticism. Officials concede that approximately 5.2 million pages of Epstein related material remain under review, requiring the mobilisation of 400 lawyers across four departmental offices.

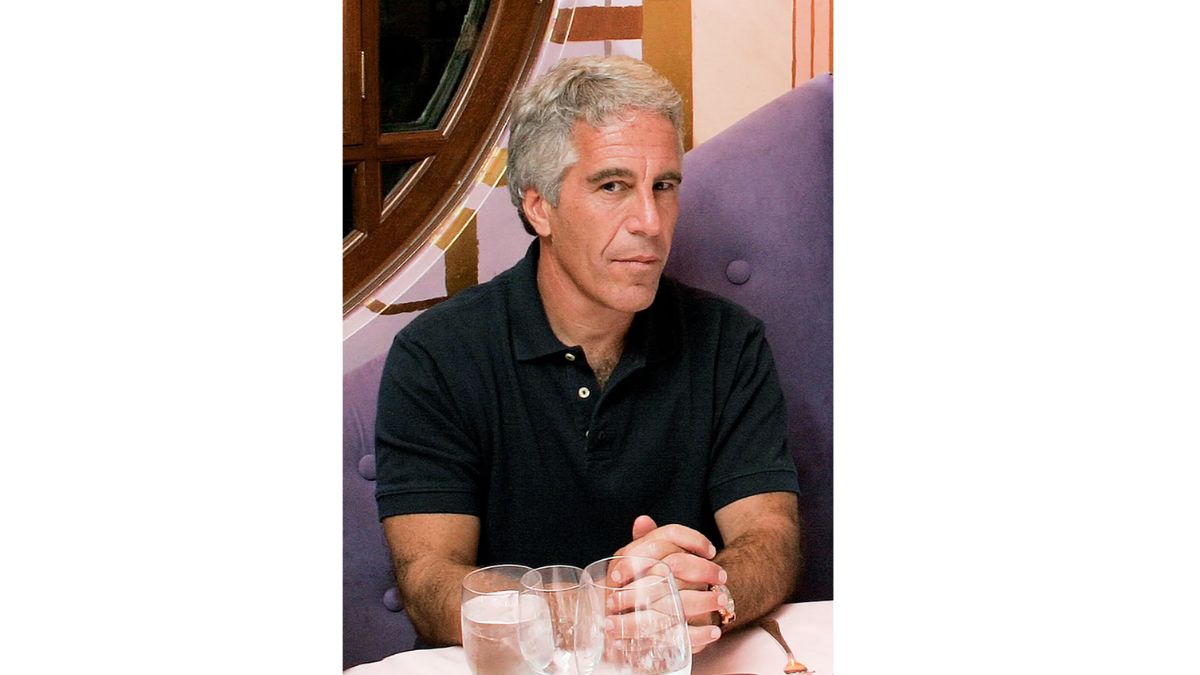

This scale is unprecedented, but so too is the public interest. Epstein’s crimes, and the network of enablers surrounding him, have generated years of suspicion that powerful individuals remain shielded by opacity and procedural delay.

While the Justice Department maintains that the review is necessary to protect victim privacy, grand jury secrecy and due process, the optics are damaging. Each extension reinforces the perception that the system is structurally incapable of delivering timely transparency when the subject matter implicates wealth, influence and institutional failure.

Separation of powers or institutional self protection

The department’s letter emphasises separation of powers, warning against judicial overreach into executive functions. This argument resonates strongly within American constitutional law, where courts are wary of supervising prosecutorial discretion.

Yet separation of powers cuts both ways. Congress enacted the disclosure requirement precisely because it judged executive self regulation insufficient in this context. When lawmakers from opposing parties converge on a demand for independent oversight, it reflects not partisan theatre but systemic distrust.

The Justice Department’s refusal to countenance even limited external supervision risks appearing less like constitutional vigilance and more like institutional defensiveness.

The Maxwell case and its shadow

Any analysis must also account for the legal posture of the underlying case. Ghislaine Maxwell is serving a 20 year sentence for facilitating Epstein’s abuse of underage girls. The criminal proceedings are formally concluded, but the documentary legacy of the investigation continues to reverberate.

The department argues that continued judicial involvement in document release related to a closed criminal case is procedurally improper. Critics counter that closure of prosecution does not extinguish the public interest in understanding how the crimes were enabled and overlooked.

This tension between finality and transparency is not easily resolved, but it lies at the heart of the current impasse.

A narrow legal victory, a broader institutional problem

If Judge Engelmayer accepts the Justice Department’s arguments, the ruling will almost certainly be legally defensible. Standing doctrine, limits on amicus participation and the absence of explicit statutory authority all favour the department’s position.

But legality does not equate to legitimacy. The Epstein files controversy illustrates a growing gap between what institutions are permitted to do and what the public expects them to do in cases involving systemic abuse and elite impunity.

The refusal to allow independent supervision may preserve executive autonomy, but it does little to restore confidence in a process already viewed with deep suspicion.

Lawful resistance, lingering doubt

The Justice Department’s request to deny a special master is grounded in orthodox legal reasoning. Yet the Epstein case is not an ordinary matter, and it is precisely this extraordinariness that continues to test the limits of legal doctrine.

As the courts weigh questions of standing and authority, the larger issue remains unresolved. In a system built on public trust, transparency delayed is transparency diminished. The law may ultimately side with the department, but the legitimacy deficit surrounding the Epstein files is unlikely to be resolved by procedural victory alone.

In that sense, the real trial is not unfolding in a courtroom, but in the court of public confidence.