- 1:11 PM (IST) 20 Jan 2026Latest

Europe live legal update: Chagos Agreement under the microscope

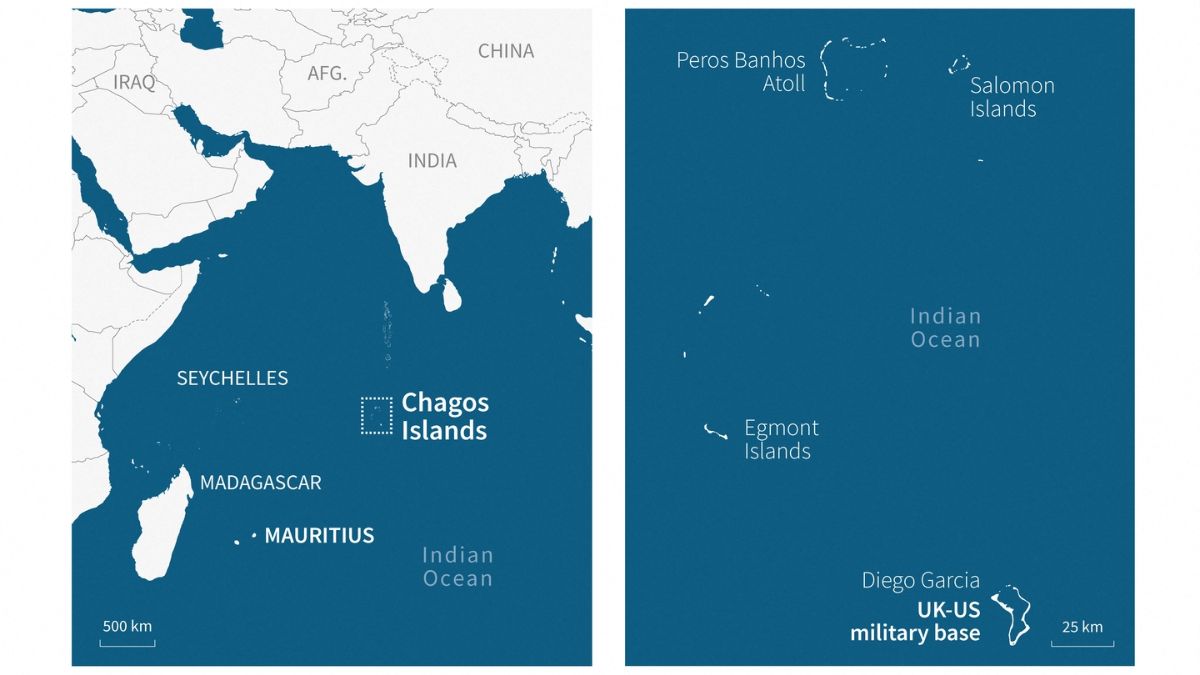

The United Kingdom’s decision in May 2025 to cede sovereignty over the Chagos Islands to Mauritius while leasing Diego Garcia for ninety nine years to continue operating a joint United States United Kingdom military base is one of the most legally consequential territorial settlements undertaken by Britain since the end of empire. Far from being a routine diplomatic adjustment, the agreement represents the collision of decolonisation law, human rights obligations, military strategy, alliance politics and long delayed accountability for one of the darkest episodes of post war British colonial policy.

The United Kingdom’s decision in May 2025 to cede sovereignty over the Chagos Islands to Mauritius while leasing Diego Garcia for ninety nine years to continue operating a joint United States United Kingdom military base is one of the most legally consequential territorial settlements undertaken by Britain since the end of empire. Far from being a routine diplomatic adjustment, the agreement represents the collision of decolonisation law, human rights obligations, military strategy, alliance politics and long delayed accountability for one of the darkest episodes of post war British colonial policy.

It has also become a focal point in the current Greenland crisis, after Donald Trump cited the Chagos settlement as evidence of what he calls British weakness and as justification for his own ambition to acquire Greenland. This makes the legal character of the Chagos agreement not merely a historical matter, but a live precedent with global ramifications.

To understand its significance, it is necessary to examine precisely what the United Kingdom agreed to, why it did so, and how the agreement fits within binding international legal obligations that London could no longer evade.

The agreement signed in May 2025 transferred sovereignty over the entire Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius, while simultaneously leasing the largest island, Diego Garcia, to the United Kingdom for ninety nine years. The purpose of the lease is to allow the continued operation of the joint US UK military base that has existed there since the Cold War and which remains strategically central to American and British power projection across the Middle East, East Africa and the Indian Ocean.

Financially, the arrangement is substantial. The United Kingdom committed to establishing a forty million pound fund for Chagossians who were forcibly expelled from the islands in the late nineteen sixties and early nineteen seventies. In addition, Britain agreed to pay Mauritius at least one hundred and twenty million pounds annually for the duration of the lease, amounting in cash terms to a minimum of thirteen billion pounds over ninety nine years.

Politically, the deal followed years of negotiations initiated under the previous Conservative government, triggered by the 2019 advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice.

That opinion was legally devastating for the British position.

The Court concluded that the detachment of the Chagos Islands from Mauritius in 1965, three years before Mauritian independence, violated the right of the Mauritian people to self determination. It held that the process of decolonisation had not been lawfully completed and that the United Kingdom was under an obligation to bring its administration of the archipelago to an end as rapidly as possible.

While advisory opinions are not formally binding, their authority is immense. The UN General Assembly subsequently adopted resolutions demanding British withdrawal, and international support for the Mauritian claim became overwhelming. Britain found itself increasingly isolated, defending a territorial arrangement rooted in colonial coercion and strategic convenience.

From a legal perspective, the United Kingdom’s room for manoeuvre had evaporated.

The right to self determination is not a discretionary principle. It is enshrined in the United Nations Charter and recognised as a fundamental norm of international law. The forced separation of colonial territory to serve the strategic interests of a metropolitan power is precisely the abuse that the decolonisation framework was designed to prevent.

Compounding this illegality was the manner in which the Chagossian population was treated. Britain bought the islands for three million pounds in 1968 and forcibly displaced up to two thousand inhabitants to make way for the military base. They were removed to Mauritius and the Seychelles in conditions that caused widespread poverty, social disintegration and long term trauma.

International human rights law, even as it stood at the time, prohibited mass forced displacement without lawful justification, due process or adequate compensation. By contemporary standards, the episode constitutes a grave breach of fundamental rights, including the prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment and the right to family life and home. It is widely described by legal scholars and human rights bodies as a crime against humanity.

Against this background, the 2025 agreement can be understood as a form of delayed legal compliance.

The establishment of the forty million pound fund for Chagossians is an implicit recognition that previous compensation schemes were grossly inadequate. The annual payments to Mauritius reflect the economic value of continued military use of Diego Garcia and acknowledge that Britain no longer holds lawful title to the territory.

Yet the structure of the agreement also reveals the enduring dominance of strategic necessity over justice.

By retaining a ninety nine year lease on Diego Garcia, the United Kingdom and the United States have ensured that the base will operate for at least another century. For Mauritius, the restoration of sovereignty is symbolically and legally transformative. For the Chagossians, meaningful return remains uncertain while the island most capable of supporting resettlement remains militarised.

Legally, however, the lease arrangement is orthodox. International law permits a sovereign state to lease territory for military purposes. The crucial distinction is that sovereignty now resides with Mauritius, not Britain. The base exists by consent, not by colonial fiat.

This distinction lies at the heart of the present controversy.

Donald Trump’s assertion that the United Kingdom is “giving away” Diego Garcia ignores the legal reality that Britain was under an obligation to relinquish sovereignty. The only lawful alternative would have been continued violation of international law.

Former Conservative leaders characterised the deal as “national self harm” and argued that it left Britain vulnerable to Chinese influence because of Mauritius’s diplomatic relationships. That argument collapses under legal scrutiny.

First, Mauritius is a sovereign state entitled to conduct its foreign relations. Second, any attempt by Britain to retain territory unlawfully in order to counter hypothetical Chinese influence would itself constitute a breach of the prohibition on intervention and of the right to self determination. Third, the continued presence of a major US military base under a long term lease severely limits any realistic prospect of hostile control.

Keir Starmer’s defence of the agreement was legally accurate, even if politically contentious. He stated that there was “no alternative” to the deal, that it was “part and parcel of using Britain’s reach to keep us safe at home”, and that it was “one of the most significant contributions that we make to our security relationship with the United States”.

From a legal standpoint, he was correct.

Once the International Court of Justice had spoken and the General Assembly had acted, Britain’s options were narrowed to compliance or continued defiance of the international legal order. The latter would have exposed the UK to sustained diplomatic isolation, reputational damage and potential legal action in other forums.

The Chagos agreement therefore stands as a case study in how international law, even when long ignored, can eventually compel powerful states to change course.

It is precisely this reality that now unsettles Trump.

By framing the agreement as weakness, he is attacking not a British policy choice, but the authority of international law itself. His logic is that strategic utility should override sovereignty, that military bases should confer territorial entitlement, and that decolonisation obligations are optional.

This logic is identical to that underpinning his demand for Greenland.

Greenland, like Chagos, is a territory with a distinct population and a defined legal status under international law. Denmark’s sovereignty over Greenland is lawful and uncontested. The people of Greenland hold the right to self determination. The existence of strategic interests, including military installations, does not create any legal entitlement for the United States to acquire the territory.

The Chagos agreement demonstrates the opposite of what Trump claims.

It demonstrates that even a former imperial power must relinquish unlawfully held territory, even when vital military assets are involved. It demonstrates that strategic necessity does not extinguish sovereignty. It demonstrates that bases can exist without ownership. And it demonstrates that historical injustice, even when politically inconvenient, generates enduring legal obligations.

It is also a warning.

The financial cost to the United Kingdom, at least thirteen billion pounds over the life of the lease, is the price of having delayed compliance with international law for decades. Had Britain respected self determination in the nineteen sixties, there would have been no need for compensation funds, annual payments or reputational rehabilitation.

For European states now facing American pressure over Greenland, the lesson is stark. Compliance with law early is cheaper than defiance. Sovereignty conceded under coercion is not lawful settlement but a precedent for future demands.

The Chagos agreement is therefore not a story of weakness. It is a story of belated legal correction, achieved at enormous financial and moral cost.

In the current geopolitical climate, it has become something else as well: a legal shield.

It stands as authoritative evidence that territory is governed by law, not by military convenience. That bases do not equal ownership. That self determination is not negotiable. And that even the closest allies cannot rewrite sovereignty through pressure.

If that lesson is forgotten in Greenland, the world will return to an era where the map is drawn by those with the strongest armies and the deepest pockets.

The Chagos settlement shows where that road leads.

It leads not to security, but to decades of litigation, human suffering, international condemnation and a final reckoning that no power, however great, can ultimately avoid.