- 1:00 PM (IST) 20 Jan 2026Latest

Europe live legal updates: Starmer confronts Trump on Greenland tariffs

The direct intervention by Prime Minister Keir Starmer in response to Donald Trump’s threat to impose sweeping tariffs on NATO allies over Greenland marks one of the most consequential moments in modern transatlantic diplomacy. What is unfolding is no longer a conventional trade dispute or a clash of personalities. It is a structural confrontation between the legal architecture of collective security, the prohibition of coercive economic warfare between allies, and an American presidential doctrine that openly links tariffs, military pressure and territorial acquisition.

The direct intervention by Prime Minister Keir Starmer in response to Donald Trump’s threat to impose sweeping tariffs on NATO allies over Greenland marks one of the most consequential moments in modern transatlantic diplomacy. What is unfolding is no longer a conventional trade dispute or a clash of personalities. It is a structural confrontation between the legal architecture of collective security, the prohibition of coercive economic warfare between allies, and an American presidential doctrine that openly links tariffs, military pressure and territorial acquisition.

Starmer’s warning to Trump that tariffs against NATO allies are “wrong” was delivered during a telephone call on Sunday, alongside parallel conversations with the Danish prime minister Mette Frederiksen, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen, and NATO secretary general Mark Rutte. Downing Street confirmed that in every call Starmer reiterated two central propositions: that security in the high north is a collective NATO responsibility, and that using tariffs against allies pursuing that collective security violates the very logic of the alliance.

These statements place the United Kingdom squarely at the centre of an unprecedented legal and strategic crisis.

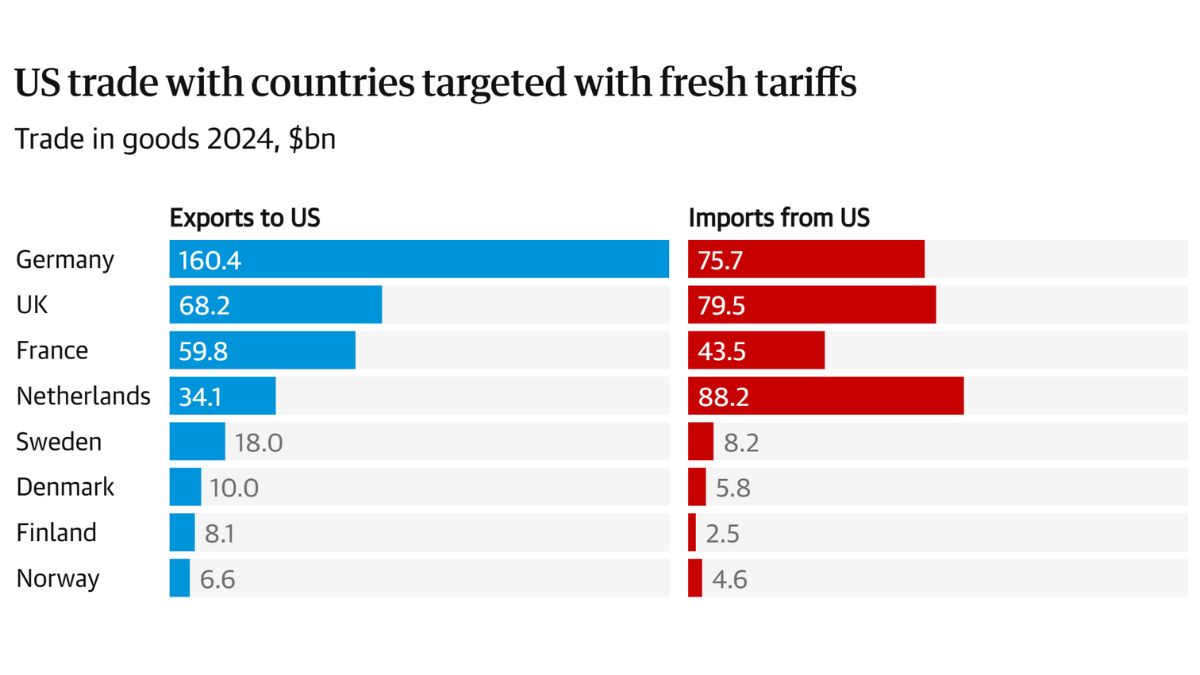

At issue is Trump’s declared intention to impose 10 percent tariffs from 1 February on the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, the Netherlands and Finland, rising to 25 percent on 1 June if a deal to transfer Greenland to the United States is not reached. He has further threatened sanctions against countries, including the UK, that have deployed troops to Greenland in response to American statements about its future.

The joint statement by the affected states that Trump’s threats “undermine transatlantic relations and risk a dangerous downward spiral” is not diplomatic exaggeration. It is a precise description of conduct that, in legal terms, verges on economic coercion prohibited by international law.

Under the Charter of the United Nations, states are obliged to refrain not only from the use of force but also from intervention in the internal or external affairs of other states. While economic pressure is not per se unlawful, the International Court of Justice has repeatedly affirmed that coercive measures designed to compel a sovereign state to surrender core elements of its political independence or territorial integrity breach the principle of non intervention.

Tariffs imposed explicitly to force Denmark and its allies to accept the transfer of Greenland would satisfy that definition. Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark, and its status can only be altered by Denmark and the Greenlandic population through lawful constitutional and international processes. No third state possesses a legal entitlement to demand negotiations over its acquisition, still less to threaten punishment for refusal.

The NATO dimension deepens the illegality.

The North Atlantic Treaty is not merely a political compact but a binding international agreement. Article 1 commits all members to settle disputes by peaceful means and to refrain from the threat or use of force inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations. Article 2 commits them to strengthen free institutions and promote stability and well being. Article 5 establishes collective defence.

Nowhere does the treaty permit a member state to apply economic sanctions or punitive tariffs against other members for participating in alliance defence measures.

On the contrary, the deployment of troops to Greenland by European allies is a lawful exercise of collective security cooperation. Greenland, as Danish territory, is part of the NATO strategic environment in the high north. Responding to perceived threats to its status or security falls squarely within the alliance’s remit.

Trump’s threat to sanction allies for doing precisely what NATO was designed to do is therefore legally incoherent. It converts collective defence into a trigger for punishment. If accepted, it would render Article 5 meaningless, since any allied response to aggression could be met with economic retaliation by the alliance’s most powerful member.

Starmer’s formulation that “applying tariffs on allies for pursuing the collective security of NATO allies is wrong” is not merely political. It is an accurate statement of treaty logic and legal obligation.

The prime minister’s decision to cancel a domestic event on the cost of living in order to deliver an emergency Downing Street statement underlines the gravity with which the British government views the situation. At that statement, Starmer is expected to reiterate the UK’s disappointment at the US tariff threat, and to align the UK fully with European opposition to Trump’s plan.

At the same time, he is not expected to announce retaliatory tariffs or countermeasures. This restraint reflects a calculated legal and diplomatic strategy.

Under World Trade Organization law, unilateral retaliatory tariffs without following dispute settlement procedures can themselves constitute violations. The European Union and the UK have legal pathways to challenge US measures through the WTO, though the system is already strained by years of American obstruction of appellate appointments. Immediate retaliation would risk escalation and could weaken the legal position of the complainant states.

Starmer’s approach therefore emphasises legal principle and alliance unity rather than reciprocal economic warfare.

The political context in Britain is complex. Every major UK party, including Reform UK led by Nigel Farage, has condemned Trump’s tariff threats. The Liberal Democrats are demanding an emergency parliamentary debate and the abandonment of a pharmaceuticals agreement with Washington. Some Labour MPs argue that the UK should adopt a more overtly European aligned stance, accepting that a normal relationship with the current US administration may be impossible.

Lisa Nandy, speaking for the government, articulated the legal red line with exceptional clarity. She stated that the UK position on Greenland is “non negotiable”, that the future of the territory is for the people of Greenland and the people of the Kingdom of Denmark alone to determine, and that this view has been communicated directly to American officials.

This is a textbook statement of international law.

The right of peoples to self determination is enshrined in the UN Charter and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Greenland’s population cannot be transferred as part of a geopolitical transaction between states. Any attempt to do so under economic or military pressure would be void under international law and would engage the responsibility of the states involved.

Starmer’s insistence on maintaining close ties with the United States, and his acknowledgement of the benefits that his personal rapport with Trump has brought in earlier trade arrangements, reflects the reality of power politics. He has invested heavily in that relationship, including by offering Trump an unprecedented second state visit to the UK and by positioning Britain as a bridge between Washington and other NATO members over Ukraine.

Legally, however, personal diplomacy cannot override treaty obligations or fundamental norms.

The current crisis exposes the limits of relationship based foreign policy when confronted with a doctrine that openly treats tariffs, military threats and territorial acquisition as interchangeable instruments.

Trump’s approach collapses the distinction between trade law, security law and the law of territorial sovereignty. In doing so, it destabilises every institutional framework built since 1945 to prevent precisely this fusion of coercion and expansionism.

The joint statement by European states warning of a “dangerous downward spiral” is legally well founded. Once tariffs are used to extract territorial concessions, the door is opened to a world in which economic power substitutes for armies, and sovereignty becomes conditional upon commercial resilience.

For NATO, this would be existential. An alliance in which the leading power economically punishes members for complying with alliance security policy cannot function as a collective defence organisation. It becomes a hierarchy enforced by coercion.

Starmer’s intervention therefore carries significance far beyond British trade interests. It is an attempt to reassert the legal grammar of the international system: that alliances are voluntary and equal, that territory is not negotiable under pressure, that trade measures are governed by law, and that security cooperation is not a pretext for punishment.

Whether this stance can moderate the White House remains uncertain. Officials hope that Starmer’s relationship with Trump may encourage a climbdown. Yet even this hope is an implicit admission of the fragility of the legal order when confronted with personalised power.

What is certain is that the Greenland crisis has become a test case.

If tariffs can be imposed on NATO allies to compel acceptance of territorial transfer, then the prohibition on coercive diplomacy is effectively dead. If the future of Greenland can be decided in Washington rather than Nuuk and Copenhagen, then self determination is reduced to a slogan. If collective defence can be punished as disloyalty, then NATO becomes a legal fiction.

Starmer has chosen to draw the line publicly and legally.

In doing so, he has framed the dispute not as a quarrel between governments, but as a confrontation between two models of world order: one governed by treaties, sovereignty and law, and another governed by leverage, pressure and the preferences of the strongest.

The outcome will shape not only the fate of Greenland, but the credibility of the legal system that has restrained territorial ambition for nearly eight decades.