In a medium as dynamic and influential as anime, representation matters—especially when it comes to female characters. Over the years, the rise of the “strong female character” has become a defining feature in many popular series. From Mikasa Ackerman slicing through Titans to Erza Scarlet switching between armors mid-battle, these characters exude power. But beneath the surface lies a question that keeps resurfacing:

Are these women really strong—or are they just fanservice with a sword?

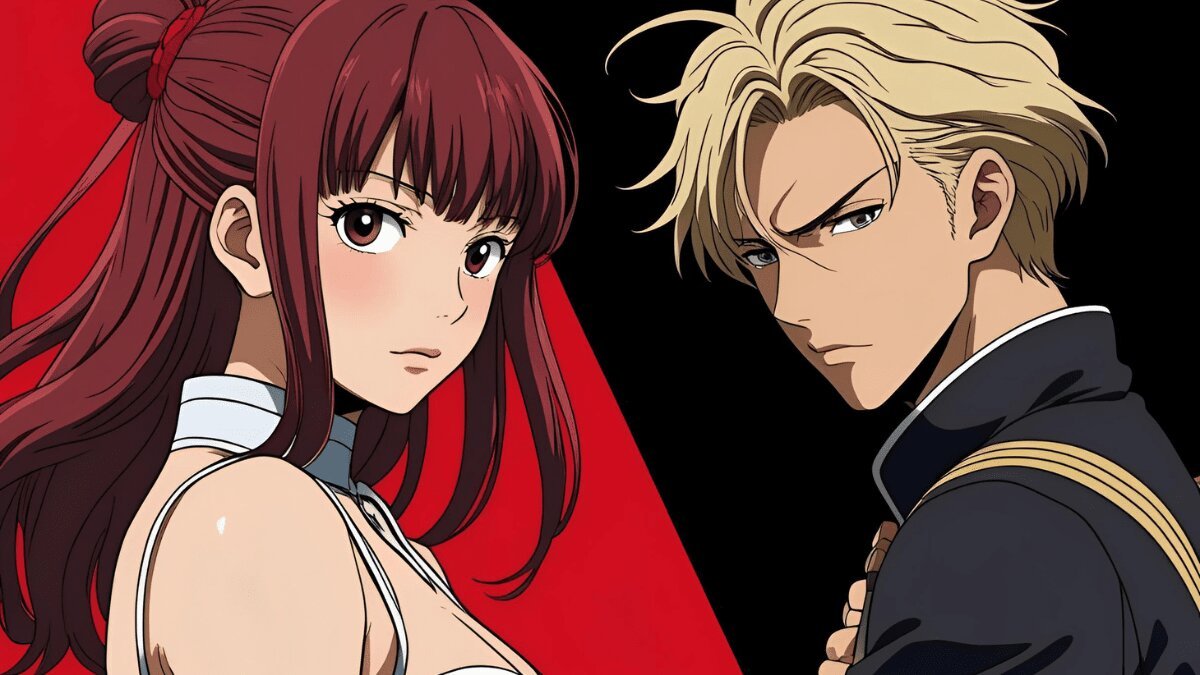

This dilemma taps into a broader issue: strength in female characters is often over-simplified or sexualized, reduced to tight costumes, impossible body physics, and a single emotional dimension—usually stoic or rage-fueled. For every Motoko Kusanagi who challenges gender norms and philosophical constructs, there’s a Zero Two whose strength is overshadowed by suggestive framing and oversexualization.

So, what does it truly mean for a female character to be strong in anime? Is she written with complexity and agency—or designed to be ogled in motion?

In 2025, fans want more than just girls who can fight—they want women who can lead, grow, fail, and succeed on their own terms. Let’s dive into what makes a strong female character truly powerful—and where anime still falls short.

The Checklist of “Strong Female Character” Tropes

Often, strong women in anime are built around a narrow set of tropes:

-

The Stoic Warrior: Think Mikasa Ackerman or Saber. Rarely emotional, hyper-competent in combat.

-

The Femme Fatale: Like Makima or Faye Valentine—seductive, dangerous, unreadable.

-

The Emotionally Broken Girl: Often strong due to trauma, like Asuka Langley or Homura Akemi.

-

The Fanservice Fighter: Ryuko Matoi, Esdeath, or Darkness—visibly powerful but hyper-sexualized.

The issue arises when strength is visual rather than narrative. Is a character strong because she overpowers men? Or because she has inner resilience, leadership, and depth?

When Power is Just a Costume

Let’s talk about visual design—because anime is a visual medium, and how female characters look often influences how they’re perceived.

Characters like Erza Scarlet are undeniably powerful. But her design includes exaggerated curves, revealing outfits, and “armor” that wouldn’t protect a kitten. Shows like Kill la Kill even parody this trope—but ironically contribute to the same problem.

The real question becomes: is her power there for the plot—or the camera?

-

Makima from Chainsaw Man is alluring and intimidating—but her sexual appeal is intentionally manipulative, raising questions about whether she’s a narrative tool or a subversion.

-

Zero Two in Darling in the Franxx toes the line between tragic heroine and fetishized symbol.

These characters blur the line between empowerment and objectification, especially when framing and fanservice distort their original intention.

The Problem with “Strong” as a One-Note Identity

Strength isn’t just about physical prowess. Emotional resilience, moral conviction, empathy, and complexity matter too. Yet, many female characters are denied emotional arcs in favor of being constantly “badass.”

Take Sakura Haruno, often criticized for her lack of impact in Naruto. She begins with emotional depth but is later sidelined, especially compared to Naruto and Sasuke’s development. Meanwhile, Hinata is strong in resolve but is reduced to a love interest by the finale.

Anime often falls into the trap of making women strong only in relation to men—supporting them, loving them, or proving themselves against them. Rarely are they strong for themselves.

The Standouts: When Anime Gets It Right

Not all is doom and gloom. Many characters break the mold and deliver real representation:

-

Motoko Kusanagi from Ghost in the Shell: A philosophical leader, grappling with identity and agency in a synthetic world.

-

Clare and Teresa from Claymore: Fighters with deep emotional trauma and layered motivations.

-

Nico Robin from One Piece: Intelligent, deadly, emotionally complex, and written with grace and autonomy.

-

Revy from Black Lagoon: Deeply flawed, unpredictable, and layered, proving that strength isn’t about being “likable.”

These characters demonstrate that anime can handle strong female characters with nuance—it just chooses not to, often.

Are Studios Listening in 2025?

As more women enter anime fandom and production roles, there’s a visible shift. Shows like Jujutsu Kaisen and Demon Slayer introduce women like Nobara Kugisaki and Mitsuri Kanroji, who exhibit power, emotionality, and humor without being reduced to one trope.

Yet, the industry still struggles with:

-

Marketing female characters through figure sales and swimsuit specials

-

Reducing emotional depth to “moe” or “dere” archetypes

-

Avoiding story arcs that allow for female growth independent of men

Change is slow, but it’s happening—because fans are demanding it.

What Can Fans Do?

Fans play a huge role in shaping which characters succeed and which tropes die. Here’s how you can push for better:

-

Support nuanced female-led stories (e.g., Violet Evergarden, March Comes in Like a Lion)

-

Critically engage with your favorites—love Mikasa, but call out when she’s underwritten

-

Challenge gatekeeping—make space for conversations about sexism, design, and voice

-

Create content—fanfic, videos, reviews that uplift well-written female characters

Fandom is power. What you watch, share, and talk about matters.

Conclusion: Beyond the Sword and the Skirt

So, are strong female characters just fanservice with a sword?

Sometimes. But they don’t have to be.

Anime has the potential to portray women as fully-realized beings—capable of strength, vulnerability, rage, love, and contradiction. The more we demand characters who are people first and archetypes second, the closer we get to meaningful, respectful representation.

Strength isn’t just about who draws the sword—it’s about who writes the story, and who dares to wield the pen.